Research

The importance of epistasis

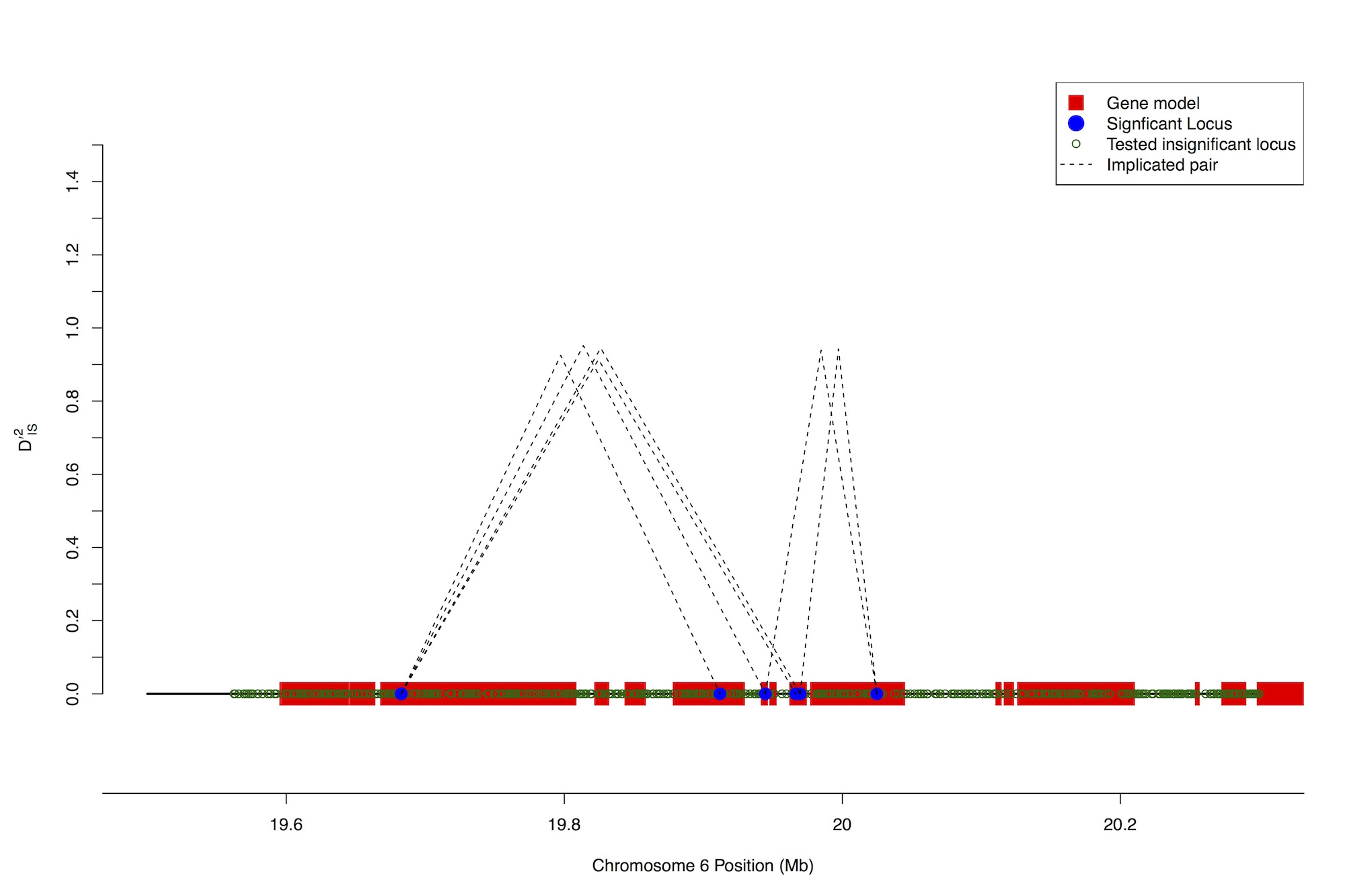

Biochemical analyses routinely demonstrate that genes interact in complex networks and pathways to generate chemical products necessary for development. However, the importance of these epistatic interactions with respect to quantitative traits remains unknown. This is despite the enormous amount of research, both theoretical and empirical, that has been devoted to gaining a better understanding of the phenomenon. One of the primary reasons that epistasis is poorly understood is that unlike when testing the effect of variants at individual loci, testing the effects of specific combinations of variants at multiple loci scales much more rapidly than the number of loci being tested. This quickly generates a lack of statistical power, and is often referred to as the “small n, large p” problem. Our lab is interested in developing and applying methods to avoid this problem by reducing the space of parameters that we are interested in testing. In the figure shown, we demonstrate as an example one approach we have taken to achieve this, which involved looking for selection on particular epistatic combinations by limiting our search space to only linked cases of epistasis. In the figure shown, dashed lines represent connections between distinct loci that are putatively epistatic.

Genomic prediction

Techniques such as quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping, Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS), and genomic selection (a.k.a genomic prediction) all focus on relating genotypes and phenotypes is present-day populations. Conversely, selection-mapping and/or scans for selection focus on identifying loci that were historically important during past selection, without necessarily incorporating any phenotypic information. Therefore, results from selection mapping and other evolutionary studies represent independent information that may prove beneficial when incorporated into a genomic-prediction framework. We are working to develop and implement methods to accelerate plant (and animal) improvement by incorporating evidence of past selection into prediction models that emphasize present genotype-phenotype relationships to develop better populations in the future.

Response to selection

Before the development of genomic selection, phenotypic selection was the primary technique implemented for improving plant and animal populations. Because of this, a multitude of selected maize and other crop populations exist that can be studied to gain a better understanding of how selection impacts the genetic makeup of populations. However, in crops most of these resources were selected with the primary goal of immediate plant improvement, and therefore they are not optimized for evolutionary studies. For instance, large population sizes, replication, and rapid LD-decay are three factors that are missing from many existing selected populations. We are beginning a new long-term selection study designed to facilitate down-stream genetic studies. Important details such as the trait we will select are still being determined (as of July 2015), so stay tuned for exciting updates! Down the road, we will use this population, coupled with the existing resources previusly mentioned, to do mapping, investigate gene action, evaluate effect sizes, and generally improve the understanding of how crops such as maize respond to selection.

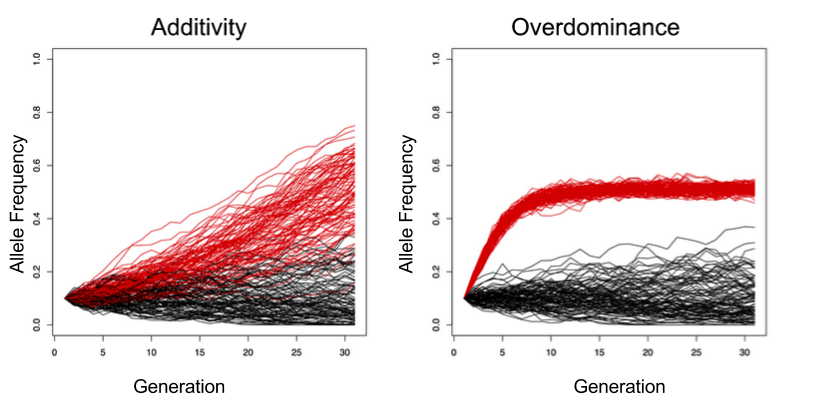

For example, the figure above depicts simulations showing how allele frequencies are expected to change across generations under drift (black lines, both panels), selection at a locus that is additive (red lines, left panel), and selection at a locus that displays overdominance (red lines, right panel). By tracking factors such as allele frequency change over the course of a replicated selection experiment, we will be able to determine which of these potential gene-actions is at play.